On Monday afternoon, the 13th of May, 2013, the GSRL research team (Paris, France) had the opportunity to listen to a fascinating in-depth analysis of "the price of enthusiasm: British and Commonwealth Methodism in the "Global City".

On Monday afternoon, the 13th of May, 2013, the GSRL research team (Paris, France) had the opportunity to listen to a fascinating in-depth analysis of "the price of enthusiasm: British and Commonwealth Methodism in the "Global City".

The main point of Matthew Wood's topic was to study interactions at a local Methodist level in London, in order to understand better the cultural challenges of remixing Methodist identity today through the impact of migrations.

Matthew Wood is a British scholar attached to the school of sociology, social policy and social work (Queen's University Belfast), currently visiting scholar in France where his research is welcomed as a booster towards more comparative studies on religious change in global cities like London and Paris.

For the purpose of his research, he has conducted 39 interviews, led 2 large London surveys and spent 15 months in 5 different Methodist congregations in London.

Historically, promoters of what is called today methodism wanted the Church of England to reach out to relegated sections of the population. Influenced by continental pietism, it started as a strong revival movement, gaining lots of converts.

Historically, promoters of what is called today methodism wanted the Church of England to reach out to relegated sections of the population. Influenced by continental pietism, it started as a strong revival movement, gaining lots of converts.

But it gradually ended up, in the course of the XXth Century, as a routinized and bureaucratized denomination, losing members. "A propensity to sing hymns loudly is probably the only survival of past emotions" (quoted in Bryan Turner, "Belief, ritual and experience: the case of Methodism", Social Compass, 18 (2), p.197).

As Matthew Wood rightly emphasizes, we should study more declining churches. Not just growing churches. Things that are not growing are not of less intristic interest than things that are growing.

Matthew Wood's focus is to highlight the contrast between a declining and gentryfied Methodist sub-culture in UK and a very lively Methodist faith coming from immigrants, particularly from the Carribean island of Montserrat, which he as chosen as a case-study.

Matthew Wood's focus is to highlight the contrast between a declining and gentryfied Methodist sub-culture in UK and a very lively Methodist faith coming from immigrants, particularly from the Carribean island of Montserrat, which he as chosen as a case-study.

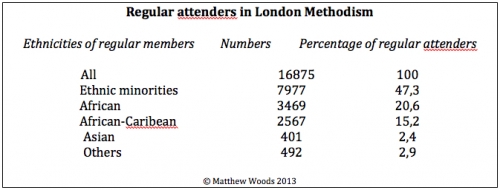

As figures illustrate below, Caribbean and African immigrants are today far more involved in the Methodist church than local white "traditional" London affiliates.

Half of today's Methodist churches in London with a majority of Black people

Nearly half of Methodist churches in London can be defined today (2013) as multiracial with a majority of Black people. In many ways Commonwealth methodism has retained its religious distinctiveness: among the distinctives shared by Methodists from a Carribean and African background, there is a strong emphasis on laity, voicing of moral jugement, focus on the Bible, and regular attendance.

The encounter between British methodism and Commonwealth Methodism reveals striking contrasts in terms of attendance and identity.

A closer look at congregations reveals that while there is a big loss of "white" attendance within the last decades, there is a rise of immigrant worshipers, many of them coming with a strong Methodist background, including coming from Montserrat, where Methodism is widely rooted in the local population. This illustrates the contrast between a secular European Global City and the strongly religious identity of immigrants.

Marginalization of immigrants

However, what the study by Matthew Wood illustrates is while there is a British discourse giving value to diversity, the reality on the field is characterized by the marginalization of immigrants. On a theoretical level, Matthew Wood refers here to Ghasan Hage 's book (1998), White nation: fantasis of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society, Annandale, Pluto Press, Australia.

However, what the study by Matthew Wood illustrates is while there is a British discourse giving value to diversity, the reality on the field is characterized by the marginalization of immigrants. On a theoretical level, Matthew Wood refers here to Ghasan Hage 's book (1998), White nation: fantasis of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society, Annandale, Pluto Press, Australia.

In this book, the author analyses the fact that Multiculturalism tends to confine migrants to passive citizens. They are objects to be celebrated by the liberal elite while on the ground, relegation is still there.

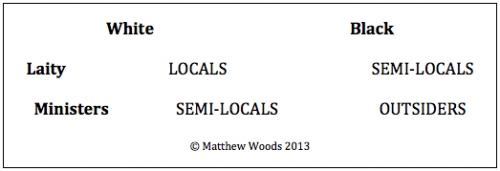

In terms of responsibility share, "whites" remain largely dominant in today's London Methodism, and quite reluctant to give more place to Carribean or African-born new members. The model below illustrates this contrast : Blacks tend to be marginalized as outsiders in the Church staff and responsibility share.

Migrants are perceived as semi-locals. Their dark skin marks them out in the eyes of others, and indeed in their own eyes. Some of the members coming from Montserrat clearly occupied stalwarts in their home churches in Montserrat. But they could not transfer this to Britain. This is is not a capital which can be transfered. Stalwarts remain mainly white Londoners. Even within a Global City like London, the value of different forms of capital remains local-based.

The process through which members become leaders takes not a racial discourse, but it is a racial process going on anyway. In practice, most lay Methodist leaders are white Londoners, most preachers are white, and in meetings, Blacks are clearly relegated. However, Matthew Wood notices that the age factor should be considered too. White leaders are older, while many immigrants are much younger. This age gap tends to reinforce white authority, not just because of skin color or heritage, but also because of a generation gap.

The process through which members become leaders takes not a racial discourse, but it is a racial process going on anyway. In practice, most lay Methodist leaders are white Londoners, most preachers are white, and in meetings, Blacks are clearly relegated. However, Matthew Wood notices that the age factor should be considered too. White leaders are older, while many immigrants are much younger. This age gap tends to reinforce white authority, not just because of skin color or heritage, but also because of a generation gap.

This fascinating study, which reconsiders the "interaction order" within contemporary Methodism in the Global City (Ervin Goffman, "The interaction order", American Sociological Review, 1983, 48, 1-17), invites to develop comparative studies.

Comparative studies to be done with the Parisian field

As a French case-study has emphasized, local protestant communities in contemporary Paris like the Baptist Church of Avenue du Maine (link) have been strongly reshaped by immigrant newcomers, creating cultural challenges and authority issues. Both Britain and France share a strong colonial past, with lively remaining connections with their former "Empire", translated into large immigration networks between the metropolis and Black Africa and Black Carribean islands.

In both French and British capitals, Protestant denominations are confronted to mixity and interaction. Within the same churches, there is an encounter between a European trend towards minority religion in a very secular context, and an immigrant "way" of living religion as a "secular canopy" (Peter Berger).

"Whites gave me a dying God"

This contrast translates within the same Protestant denominations (whatever it is, Methodist, Baptist or Presbyterian), and is certainly not confined to Protestantism.

A few years ago, Gaston Kelman, a prominant French Catholic writer with a Cameroon background authored a book which title is: "Whites gave me back a dying God" (Les blancs m'ont refilé un Dieu moribond, Desclée de Brower).

Even if there is a part of "cliché" in this contrast between Secular Europe and the religious migrant, this is certainly a field worth of further studies like Matthew Wood's inspiring research on London Methodism.

Comments

Thanks for this insight